Celebrating 10 years of being self employed

Or: Choosing between a rock, a hard place and not falling to your death

I was laid off from Sporting News Magazine 10 years ago today. It was an incredibly great job—I traveled the country writing feature stories for a national sports magazine. In terms of career goals, that was pretty much a bullseye. I am extremely grateful for having worked there, and I choose to remember how awesome it was rather than how it ended.

Still, it did end, and it’s funny the things you remember of traumatic days. I had rented a car that morning. My boss called to tell me to attend a surprise meeting that day. That could only mean one thing, and it wasn’t good. I returned the car after less than an hour, told the person at the desk I was returning it early because I was losing my job that very day … and they still charged me full price. That was not a good start to what became my self-employed life.

In starting my writing business, I feared being adrift, alone, with nobody looking out for me, no safety net, no one to protect me when rental car companies treated me poorly. I feared what my kids and wife would think of me. I feared failing. I feared flailing. I feared falling.

Ah, hell, I feared everything. That fear consumed the first few years of my freelance life. I worked my butt off to try to beat it. If you’re looking for an essay on how to conquer that fear, you’ll have to read someone else. I have faced it, not beaten it, at least not completely.

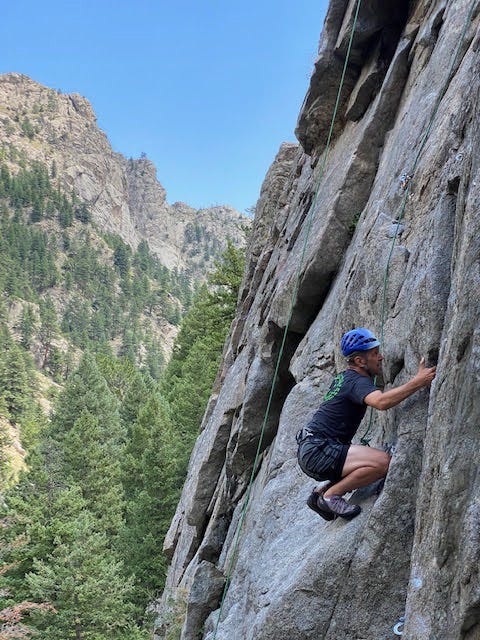

It’s still there, sometimes, more often than I like to admit, like the echo of a yell into a canyon, or the fading ripples of a rock thrown in a still pond. My life still often feels like that rock climbing picture above (me in Boulder in 2020)—I’m clinging to that wall with all my might even though there’s a rope that means I’m perfectly safe, or at least close to it.

I try to use the fear as motivation, as a reason to do something as opposed to avoiding it, and I try to face intangible fears by facing more tangible fears. My life is better because of all of that, even if at times the lessons prove exhausting.

I wrote the following a few years ago, and it remains a good summation of my self-employed life. It originally appeared in SUCCESS Magazine, won a “story of the year” award from the Society of American Travel Writers (central states chapter) and was listed in the notable mention section of Best American Sports Writing.

The door to the airplane banged open. I looked down and saw a lake, a checkerboard of farms and ribbons of gray roads stretching across rural southern Michigan. There was a man sitting to my right. I had never met him. I did not know his name. I had no idea of his credentials, other than guessing that because his title was “jumpmaster” he must be an expert. So when he barked instructions at me, I followed them.

At his behest, I swung my left leg through the open door, out of the plane and onto a step. Then I swiveled my hips so I could reach my arms out. Left hand first, I grabbed the strut that holds the wing to the body of the plane and pulled myself out.

Now I was standing outside of the airplane. While holding on to the strut with both hands, I dangled, at his command, first my right foot and then both feet off of the step they had been on. The plane was 3,500 feet off the ground and moving at 65 miles per hour. I flapped in the wind like a flag on a car antenna. A static line connected the parachute pack on my back to the plane. When I let go of the strut and fell, the static line would become taut, which would yank the parachute out.

I hoped so, at least.

As my hands strained to squeeze the struts to dust, I was, to say the least, questioning my decision making.

The jumpmaster gave one last instruction: “Let go!”

I acted like I didn’t hear him. I refused to let go.

* * *

That was June of 1994, my first month out of college. I was never that scared again until March of 2013, when I was a writer at Sporting News. One morning I got up early to drive to an assignment. My boss called to tell me I needed to attend a meeting in the office that afternoon. He would not tell me what the meeting was about, and by not telling me, he told me everything. I was going to be laid off. I returned home to squeeze the struts of my career for a few hours before being kicked out of the proverbial airplane.

I was (and remain) a married father of two, and having my wife stay home to take care of our kids was (and remains) our top priority as parents. That was no problem when I had a job. But what if I didn’t? How was I going to provide for them?

Fear sped toward me at 32 feet per second squared. I applied for 18 openings without getting so much as a rejection letter. I don’t want to sound self-defeating, but even if I had gotten a job, the journalism landscape was so bad there was no guarantee I’d keep it. I had enough of being enslaved by that fear. I decided to launch my own writing business.

There was only one problem. I had no idea how to do it.

I wore fear like a second skin. I was afraid of failing, of being told no, that I would never sell a story and that even if I did, it would be my last.

Being on my own was isolating. I thought I could learn how to run my writing business only from other writers. I was so wrong about that—so very, very wrong—that it’s embarrassing to admit I ever thought it. And I learned I was wrong in ways I never would have expected: By putting myself in dangerous situations. Slowly but surely, I started to conquer my fear of the business world by facing fears in the physical world. The lessons I learned have steeled me for whatever adventure may come, and if you’re a solopreneur yourself—or thinking of going it alone—I hope they can serve you, too.

Lesson No. 1: Understand boldness and consequences.

By the time I arrived in Winter Park, Colorado, to ride a mountain bike down a ski slope, I was mentally, physically and emotionally exhausted. I had traveled to Colorado to write about Knights of Heroes, a camp for boys whose dads died in the military. During our three-day hike early that week, two boys had to be evacuated off the mountain because they couldn’t stop throwing up.

The two mentors leading my group were fighter pilots John “Cosmo” Oglesby and Ryan “Slider” DeKok. They embodied the camp’s “be bold” philosophy. In their personal and professional lives, they crave risk taking as a means to develop toughness and resilience and to lead a fuller life. I craved comfort and certainty.

There’s a fine line, I thought, between a fuller life and riding a bike off the side of a mountain. I planned to sit out mountain biking. I had not ridden a bike in years, and I didn’t want to re-introduce myself to that activity on a ski slope. How about a paved, flat greenway first? The tension I felt encapsulated the first challenge every solopreneur faces: At some point, you just have to go, and I wasn’t ready.

But it wasn’t easy to say no. Even though I was only a journalist, after having spent four days with the boys, I felt obligated to help with the camp’s “be bold” ethos, or at least not contradict it. The boys were willing to ride down the mountain. If I chickened out, it would send exactly the wrong message. “Be bold, unless you’re scared, then never mind” stinks as an inspirational message.

I was 43 and caved to peer pressure from a bunch of teenagers.

We rode and stopped, rode and stopped, as we acclimated to the bikes and terrain. Halfway through our first run, I thought I had the hang of it—maybe it was true that you never forget how to ride a bike. The boy in front of me was holding me up. He was scared out of his mind. But he kept going. I let him ride out of sight so I could go “fast” in catching up to him.

Soon my confidence rode ahead of my ability. I hit a root and went airborne. I grabbed my brakes—too hard, as I soon found out. When the front tire hit the ground, the bike stopped, but I kept going. As I sailed over the handlebars, I had enough time to think, I’m wearing a helmet, chest pad and knee pads, so this won’t hurt very mu—BAM!

I landed on my hands, face and chest. I inventoried the pain and was shocked I didn’t have any. The only thing wounded was my pride.

The boys and I broke for lunch. Everybody crashed at least once, and we tried to one-up each other with tales of the severity. If the adventure ended right there, I would have learned a ton about facing fear, risk versus reward and being bold. But there was more yet to come.

Slider arrived looking pale: Cosmo had crashed and broken his hip. The boys and I gathered around his bed at an on-site clinic. His eyes were glassy from the painkillers and moist from disappointment. If ever there was a lesson that boldness may come with consequences, this was it. The pain was excruciating, and he spent weeks on crutches and months in physical therapy.

That was three years ago. I called Cosmo recently to ask: Was it worth it? He said he regrets breaking his hip because of how much of a burden it created for his wife and two boys, and he won’t go mountain biking anymore because he doesn’t want to risk putting them through that again. But he’s not going to back off his devotion to bold living. “Being bold doesn’t always equal going out and winning,” he says. “Sometimes you run into a brick wall. You temper it with life experience and intelligence. If you can live a bold life, more often than not, that’s going to reward you rather than punish you.”

Even when his bold decisions punish him, Cosmo says he comes out stronger—and with great stories to tell.

Lesson No. 2: Find kindred spirits.

That assignment became a turning point for me, one of many adrenaline-soaked adventures. The first fruit of that was joy. Man, I had fun. I also had long conversations with owners and guides and was shocked at how much we had in common. Our businesses were vastly different, but we faced the same challenges.

From my white-water rafting guide, I learned rivers are like clients—they follow predictable but not guaranteed patterns. I learned about the value of escapism from a map and compass instructor who for his day job works as a homicide investigator. I learned how to be tough and smart in negotiations from my firearms instructor.

And I learned about authenticity while on an ATV tour of a glacier. The owner was delightfully charming and roguish. But he was apologetic about his roguishness, like he thought he should stop being that way because he was a business owner now and business owners are Serious People Who Make Important Decisions. He dropped an f-bomb in his introductory comments before our tour and was embarrassed about it. It’s fine, I wanted to tell him, you be you. I would have been disappointed if he hadn’t dropped an f-bomb.

The common denominator among all of them—even the paragliding instructor who offered a case study in how not to treat clients—was passion. Most of the owners I talked to opened their businesses after a career in a comparatively boring field. They wanted more out of life than the corporate world offered. And they all learned running a business presents obstacles for which passion is an insufficient remedy.

Scheduling, marketing, managing staff, keeping up with social media, building a web presence, dealing with contracts and so on were mysteries to some or all of them, just like they were for me. The ones who thrive tend to focus on paths to success, not on the obstacles in their way, an approach I learned during off-road driving lessons.

Lesson No. 3: Sharpen focus for the worst of times.

I looked down and to my left, out the driver’s side window, and saw not pavement or a shoulder but a steep ravine whose bottom I could not see. I turned my eyes back to the “road”—a narrow strip of dirt slicing through western Oregon. Green and brown streaked by the windows like a forest nightmare. It felt like I was going 100 miles per hour. I glanced at the speedometer… not even 20. But I jammed the brakes anyway because I had freaked myself out.

The truck fishtailed slightly before I regained control. To slide even two feet to the left would have been catastrophic—for me, the Tacoma pickup I was driving and my two passengers, including my off-road driving instructor. To paraphrase a mashup of Ferris Bueller and my instructor: Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t slow down in the turns you’ll go careening off a cliff and die.

The key when navigating off-roading obstacles is to look where you want to go, not at the obstacle. I needed this lesson in 2017. I lost a major client, never replaced it and couldn’t sell a story to anyone. My income dropped by 40 percent. I spiraled into anger and frustration. All I could think about was how I lost that client, and all that accomplished was to guarantee I wouldn’t sell anything.

I wanted to overhaul my business, change everything, because of one setback. I got a lesson in over-reacting last summer on another off-roading adventure, this one in Dogwood Canyon in southwest Missouri. I drove the course multiple times and tried to memorize the layout so I could go faster. On the third lap, I stopped before a section that had given me trouble the first two times. Two tire tracks snaked through there, and the road was otherwise a minefield of rocks, roots and potholes big enough to give a baby a bath in.

The tire tracks were too close together for the Toyota Sequoia I was driving. I would only be able to keep my tires on one of them. The other two tires would hit the rocks, roots and potholes. It would be half easy, half difficult. I visualized where I would go, lifted my foot off the brake and coasted forward.

There was a Tacoma in front of me. That driver had it easy. The truck’s wheelbase would allow its driver to keep both tires on smooth ground. She could avoid the rocks, roots and potholes, but she didn’t even try. She bounced and heaved and buckled through the danger I was so intent on avoiding. I watched as she and her passenger jostled around inside the cabin. From 20 feet away, above the noise of the engines, I heard them laugh in pure delight as they sped away.

I had obviously overestimated the problem. I nudged the gas and followed my cautious plan anyway. I made it through safely.

I did not laugh as I did so.

Lesson No. 4: Prepare for danger.

The most memorable critique I received in my first few years as a solopreneur was from an editor who said a story I had filed would have been fine for Sporting News, but he needed something stronger. I had grown complacent and needed to push myself. One way I did that was by chasing adventure assignments. The more adventures I went on, the more risk taking—once absent from my business life—infiltrated it. I identified difficult physical situations I had struggled with to see if I could beat them and what I could learn by doing so.

I covered a dog mushing race in Alaska and couldn’t believe what those mushers endured. I grew up in Michigan. I thought I knew cold. I didn’t know squat. The first full day I spent in Alaska, it was negative 40 degrees. I had never felt my eyeballs turn cold before, but that’s what happened. I ached all over after a few minutes and had to dash back inside, and yet the dog mushers persevered through that cold all day every day. I wondered how they survived such brutal conditions, and I returned to Alaska to go to a dog mushing school to try to find out.

When I pulled into Just Short of Magic outside of Fairbanks on March 1 of last year, I tried to roll down my window to ask an employee where I should park. But my window was frozen shut. I pulled into what I guessed was a parking spot. The pavement was under three feet of snow. As I put on my gloves and balaclava, I saw a thermostat on a barn that showed the temperature was 20 below. I smiled. This was exactly what I wanted.

I stepped out of the car and stopped smiling. The cold squeezed me like shrink wrap.

I hustled into the welcome center to warm up. I stepped outside a few minutes later to pet the dogs, and because I didn’t travel 3,600 miles to stay inside when it got cold. Eleanor Wirts, the owner, walked up and greeted me warmly. She asked me to follow her inside her cabin, where she would conduct the tutorial part of the training. Usually she does that outside, but she didn’t want us to stand outside when it was negative 20. When it’s too cold for Alaskans to be outside, it’s really cold.

Indeed, the cold is an ever-present, life-threatening challenge for Eleanor, her employees and her customers. It’s not like an off-road obstacle that she can avoid. She has no choice but to endure it. Years of experience have taught her how.

Eleanor knows many customers won’t have proper gear, so she has plenty to let them borrow. Before the lesson started, Jenna, the office manager, gave my cold weather gear a once-over, as she does for every customer. On my bottom half I wore long johns, jeans, snow pants, wool socks and boots that work fine in St. Louis winters. On the top I had more long johns, a couple sweatshirts, a St. Louis-caliber winter coat, a hat, balaclava and gloves.

That was all the cold weather gear I owned. But it was not good enough. Jenna fitted me with a coat and some boots, all Arctic caliber. If I would have insisted on wearing my own, Eleanor would not have let me on the sled.

The dog mushing trail cuts deep into the Alaskan wilderness. If anything goes wrong—the sled breaks, a snow machine crashes into it, whatever—Eleanor and her customer would have to either walk back or wait for a snowmobile to come get them. That could prove fatal if they weren’t properly dressed. The danger is that real.

I put on the boots, which were so enormous they made my St. Louis boots look like flats. I zipped up the jacket, and it felt like I was wearing an oven. Eleanor and I hit the trail, and after less than a minute, I understood how dog mushers weather the cold: They are prepared for it. I would never have believed this, but negative 20 wasn’t bad.

I no longer had to fear the cold and instead I could exult in the beauty that swallowed me. I saw only four colors—the white of the snow, the blue of the sky, the green of the needles and the brown of the trees. I heard nothing but Eleanor’s commands to the dogs—no planes, no cars, no humming machines, nothing.

After an hour, we arrived back at the kennel. I peeled off Just Short of Magic’s gear, put my own back on, walked outside and was again grateful for Eleanor’s preparation as the all-too familiar chill enveloped me again. I hustled to my car, climbed in and cranked the heat. I was grateful the door hadn’t frozen shut.

Lesson No. 5: Don’t fear being afraid.

Off-roading lessons taught me to avoid obstacles. Dog mushing taught me to prepare for them. What about facing them head on? I have a lifelong fear of heights. Could I learn to conquer that? What would it teach me about running a business? I signed up for tree climbing lessons to find out.

I showed up at Adventure Tree on a scorching St. Louis summer day, more than 100 degrees warmer than when I went dog mushing. Owner Guy Mott gave me a helmet and gloves, strapped me into his rope system and taught me to climb. I pulled myself up to the first “pitch” (a tree branch wide enough to stand on 20 feet off the ground) with no problem.

But I froze when I got there. I liked climbing, but I hated standing on the pitch. When I was climbing, I could see the ropes working. When I was standing on the pitch, I had to trust that they worked. I couldn’t do it. I did not believe the ropes would catch me if I fell.

I bear-hugged the tree (even though I was tied to it) and pondered my options. Two fears fought for my attention. One of my biggest professional fears is taking an assignment and failing to complete it. If I quit climbing, that fear would come true. But I’m also afraid of heights, and if I kept going, that fear would be tested.

The story paid $1,500, so I pulled myself to another pitch and then another.

At the third pitch, I was maybe 55 feet up. My fingers shook too much to open the carabiner, a required maneuver for me to keep going. Then my legs started twitching. I waited 10 seconds, 20, 30, hoping my involuntary movements would stop. They didn’t. I had a sudden thought that I couldn’t unthink: If my involuntary shaking caused me to fall and I seriously hurt myself or died, how dumb would it sound that I fell out of a tree? My kids would carry that burden for the rest of their lives.

By now I had climbed high enough to write a story. I decided that trying to climb higher was no longer a test of courage, it was unsafe. So I gave up, short of the top, disappointed but also confident that “never give up” is actually terrible advice.

Here’s the great irony: To get out of the tree, I had to do exactly what I was afraid of: Step off the pitch. I had no choice but to trust the ropes and use them to ease myself down.

* * *

I wish I could say the end result of all of this is that I have embraced a life of permanent boldness. I haven’t. I still stare at completed story pitches to magazine editors for hours, sometimes days, sometimes weeks, before I finally decide to risk a bad answer and hit send. But there’s no doubt that surviving physical risks has taught me to take professional risks.

Last year, I cobbled together assignments for a trip to Europe spanning 16 days, five countries, six planes, six hotels and six assignments for four different publications. It was the most audacious project I’ve ever tried, by far. Early in my solopreneur life, I didn’t have the skill to put a trip like that together, and I wouldn’t have had the guts to try to pull it off regardless. Before I left, anxiety ripped me in half. I can’t do this! What was I thinking? What kind of lunatic pitches stories in France, Belgium and Italy when he has never been there and doesn’t speak any of those languages?

I looked back at the times I had been scared and realized if I got through that, I can get through this. Collectively, those experiences prepared me like Just Short of Magic’s gear had prepared me for the cold. Like off-roading, I chose to focus on executing my stories instead of what could go wrong. I also knew that even if the whole trip went horribly sideways, I’d be stronger because of it.

There’s a line between being bold and being stupid. Where is that line? I don’t know. Every time I go on an adventure, it moves. If I ever figure out where it is, I’ll write a book, sell millions of copies and spend the rest of my life on a bucket list so epic it would make Cosmo shudder. For now, I’ll look for ways to live a bold life tempered by wisdom and experience. It helps my business and my life and it’s a heck of a lot more fun than the alternative.

I actually do know where the line between bold and stupid is: At the door of an airplane. Or more specifically, the door of the airplane I was hanging out of back in ’94. I have often wondered what the jumpmaster thought when I didn’t let go. He hollered the instruction to jump again, and I finally let go.

I dropped toward Earth, 32 feet per second squared. During training, I was taught to count to 10 and then look for my parachute, as it should be yanked open by the static line by then. At no other time in my life have I cared so much about the difference between should and would. I counted to myself… got all the way to “two one-thous” and YANK—I was floating peacefully. Using the toggles to steer, I zig-zagged all the way down, watching as the checkerboard of farms and ribbons of gray roads stretching across rural southern Michigan rose to greet me. I landed dead center on the target, a peat moss pit about the size of a batter’s box.

I smiled as I touched down, grateful to be in one piece. I told everyone it was awesome and I’m sure I’ve told bigger lies but I can’t think of any. I am never, and I mean never ever, ever, not in a million years, never, ever, ever, doing that again.

Unless a client offers to pay me to write about it.