If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider recommending it to others and becoming a paid subscriber. You’ll get dispatches about travel, adventure and #dadlife that will sometimes be heartfelt and profound, sometimes peel back modern parenting life for a look inside, and sometimes be, well, whatever this is. If you support my work, I would appreciate it.

A version of this essay originally appeared at SUCCESS.com.

Don't hit yourself in the face with a hammer

The job was dangerous only the way I did it. Working for my dad’s siding business in the summer while I was in high school and college, I fell backward off a scaffold into a bush when I lost my balance pulling out a window. The bush “caught” me. I couldn’t reach the ground, and I couldn’t reach the scaffold or the ladders holding it up. I was suspended in the bush, like a fly on a spider’s web, and for a few seconds I couldn’t get out. This went on long enough for me to wonder if I’d have to yell for help before I finally managed to roll out of the bush and onto the ground.

Another time, I jumped off a scaffold after I scraped a power line. It sparked and blew out power to the house we were working on. I’m lucky the house didn’t burn down and luckier still I didn’t get electrocuted.

The closest I ever came to seriously injuring myself was while working on our own house. I was in the backyard, alone, 15 feet up on a ladder leaning against the house, tearing off the yellow siding that had uglified our house since before I was born. One nail would not budge. I yanked and pulled and pushed. Nothing. I even tried yelling swear words at it, the worst ones I knew, in every combination I could think of. That didn’t work either.

I dug the claw under the nail as deep as it would go, pushed my hip into the ladder to use my body weight as leverage and pulled down on the hammer with both hands as hard as I could. I grunted and leaned and thought I might finally have it… then the claw broke loose from the nail and THWACK!! smacked me right between the eyes.

Yes, I hit my own self in my own face with my own hammer.

Really, really, really hard.

The impact knocked me off balance—remember, I was 15 feet up on a ladder—and I started to tumble backward off of it. At the last second, I grabbed the ladder with both hands to stop myself from falling.

Whenever I screw something up—bad pitch, bad interview, yelling at my kids for no reason—I always have braining myself with a hammer to fall back on. This is not as bad as that, I tell myself.

For most of my life, I looked back on that siding work as simply a summer job. But a surprising thing happened when I went out on my own 11 years ago: I started acting like a sider again. Thirty years after I last worked for my dad, I find myself repeatedly mimicking what he did, applying lessons I didn’t even know I had learned.

***

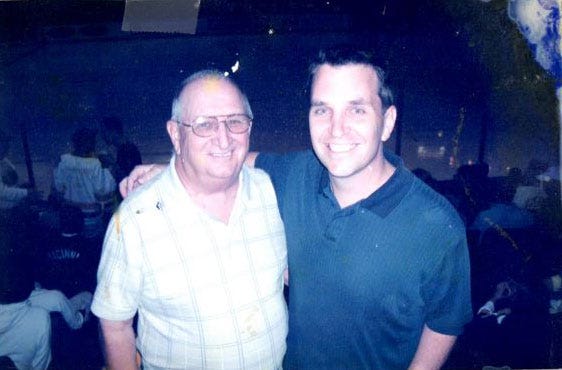

My dad, who is 85 and retired, is as old school and blue collar as they come. He would not have considered himself a solopreneur (then or now) and would make fun of me for using what he would call a made-up word. If I told him he worked in the gig economy (Siding! Windows! Trim! Gutters!) he would ask what the hell I’m talking about.

I bring all of this up to say that if you told either one of us back then that I’d be writing about what I learned by installing siding (and windows! and trim! and gutters!) that helps me run my writing business, we both would have laughed.

While I just saw it as a job, my dad saw it as an education. He hoped I’d learn that manual labor blows and go to college instead. But I did not learn that. I enjoyed the work. I liked that we made a difference in people’s lives. When we started a job, a house looked one way. When we finished, it looked completely different and always better.

But I did indeed get an education, just not in the way either one of us expected. Take, for example, dealing with clients who don’t pay on time. I’ve been extremely lucky: I’ve only had two clients stiff me. Sometimes I have to pester clients with multiple invoices. But that’s never bothered me, and I think it’s at least in part because of watching my dad deal with getting paid by customers… and because of how he paid me.

He paid me $5 an hour cash (a huge amount for a teenager in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I promise you). He was the first “client” I ever invoiced. Using a pencil, I wrote my hours day by day on a piece of cardboard torn off of boxes that siding came in. Every couple weeks, I’d give him the piece of cardboard with the hours totaled at the bottom. He paid me the next time he got paid… if he remembered. When I nagged him (circling back! checking in! following up!), he shrugged and said, “Better to owe it to you than cheat you out of it.”

No clients have tried that line on me. But I’m ready if they do.

***

There’s a saying in the trades: Measure twice, cut once. That’s important in the siding business for many reasons, not least is that you get paid the same amount whether the job takes you a week or a month. The more times you have to re-cut something, the more your margin goes down. So I learned to measure twice. I take a similar approach in writing: I work most efficiently when I think deeply about what a story will say before I type a single word. Call it think twice, write once.

This isn’t foolproof. Sometimes I measured twice and still got it wrong, and sometimes I think long, start writing, and discover either I thought wrong or didn’t think of everything. Still, I learned that being efficient means making more money while working for my dad.

Because my dad was paid by the job his whole life, he worked fast. He loved to jokingly harangue me for being slow or taking forever doing whatever task he had assigned me.

Him: What took you so long getting the siding off the back of the house?

Me: I bonked myself with the hammer and almost fell of the ladder and died.

Him:

As important as working fast was to him, he “wasted” HOURS talking to people, time he could have spent getting something done, such as helping me get out of the bushes I fell into. He chatted with customers often, but that’s not my strongest memory of him flapping his lips instead of working. No, that was at Ingram Wholesale Siding, our supplier.

We went there before starting jobs to buy material, we went there in the middle of jobs to buy more and/or pick up whatever we forgot, and we went there after jobs to drop off the excess material.

We were there at least once a week, and every time my dad and those guys would get to talking about this or that or the other thing. Blah blah blah blah they talked FOREVER.

I usually didn’t mind. The more time they spent talking, the less time I had to fall off a ladder into a bush that I had accidentally electrified.

Over the course of his career, my dad could have saved thousands of dollars and hours by zipping into Lowe’s or Home Depot. Or we could have had the material delivered instead of going to Ingram’s warehouse. (And look at me saying “we” 30 years after I last worked for him, when it was never really “we” in the first place.)

Among the many reasons I’m grateful to have worked for my dad, the biggest is that it gave me a glimpse into his life outside of being my dad. At work, and especially at Ingram’s, I saw him interact with people. I listened to how he talked to people and watched how he treated them and got to know him in a way I would have missed otherwise.

He liked talking to those guys at Ingram’s, cutting up with them, asking them questions about their lives. He would much rather have paid them a little more money than Lowe’s or Home Depot—frankly, maybe even a lot more money—because of those relationships, and because he saw them as the little guy (like himself, which he defined as good) and the big box hardware stores as the big guys (not so good).

He knew the guys at Ingram’s would take care of him. If he needed something delivered, if he needed a few extra weeks to pay them, if he needed a special order to be rushed, he knew he’d get it because of the relationships he had there.

And here I discovered the lesson as I was writing, not while thinking before: My dad was a master networker, and I only just now realized it.

***

When he wasn’t talking endlessly, my dad taught me the value of hard work. But far more important is that he taught me by example that work is part of life, and not even the most important part. We left the house at 7:30 a.m. and we were done by 4 p.m., every single day. We were home in time for dinner, every single day.

I have three brothers, and he prioritized us over work. My dad isn’t the type to say out loud, “You guys are more important to me than work.” But the way he lived his life showed it. As boys, we were all active in sports. He missed literally zero of our games because of work. The only time he missed any of my games was because he was at one of my brother’s.

My fondest childhood memories are of afternoon games of catch on our sidewalk with him and my older brother. The way the shadows hit the sidewalk in my memory, it was before dinner, which I mention to say not only did he get home in time for dinner, he had time to play before dinner, too.

I understand now in a way I didn’t then that that time was a great blessing that he chose to give. He could have been working, but he was with us instead. That’s the most important thing I learned while working with him.

“Don’t hit yourself in the face with a hammer” is a close second.